Books a College Professor Should Read on Teaching

The literature on teaching and learning is enormous; indeed, ane can easily become lost in its superabundance. And while all academics are trained to read and process huge volumes of knowledge, the bulk of us are already short on time and chronically backside in the literatures of our own fields. A deep dive into recent piece of work on educational activity is something we can scarcely observe fourth dimension for during the semester, while summers are often reserved for what might be called "academic R&R" (research and revising).

For the many among the states who face such exigencies, the following represents a short list of great (and thin!) books on topics like active learning, rubrics, teaching first-twelvemonth and showtime-gen students, form journaling, and meaningful writing projects.

This list has six books on it, just if you can read only one, read Lisa M. Nunn's 33 Simple Strategies for Faculty: A Week-by-Calendar week Resource for Teaching Beginning-Twelvemonth and Commencement-Generation Students (Rutgers, 2018). Many of your students volition be new to the university setting only because they are first-twelvemonth students; others are new to it in a more profound sense, being the first people in their families to nourish college. Both these groups – and, ultimately, all of your other students -- can benefit from the teaching strategies outlined here. It's a slender volume, but packed with great, easily implemented ideas to make both your classroom and your office hours more inviting and engaging.

To accept one example, Nunn recommends not only broadening the variety of scholars included in syllabi but also subtly highlighting these inclusions by inserting a picture of the scholars in PowerPoint presentations and so that "students come to run into female scholars and scholars of color equally a normal, routine aspect of academic life." Other excellent tips -- often simple to implement -- involve changing one's own habits of speech and educatee-teacher interactions. When my students come up to my office hours, I make it a point to avoid referring to how decorated I am so they don't feel like they're bothering me.

Nunn also suggests noting at regular intervals during your class that the material or concepts you're teaching are difficult. This is especially true (and this can be counterintuitive) if it'southward an introductory form in which students aren't building on past knowledge but inbound into unfamiliar territory. Nunn's recommendations are interspersed with anonymous, pithy quotes from students who make it clear in their own words that oft unseen stumbling blocks can hinder their learning.

In Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons From the Science of Learning (Jossey-Bass, 2016), James M. Lang sets out from the aforementioned premise mentioned in the introductory paragraph: no teacher has time to fully immerse themselves in the latest literature and radically reinvent syllabi from one semester to the next. Lang's solution is what he terms "small didactics." Rather than a wholesale change, he proposes techniques that you tin read about in the evening and implement the next morning in your lecture form.

An example is using predictions in course. Students are given some evidence of what they will run into in the next calendar week's class and asked to make their best gauge nearly its meaning. When they are exposed to it and asked to reverberate on it at greater length the following week, they remember the material more confidently.

Drawing on Lang'southward suggestion, I often ask students to wait at four or 5 brusk excerpts, images or objects drawn from the forthcoming reading and so to make an argument about how they relate. I of the most distinctive and stimulating aspects of this book is that Lang introduces each of his techniques with a brief overview of the research supporting them.

Rubrics oftentimes generate virtually as much enthusiasm as the department newsletter -- until you utilize them. Dannelle D. Stevens and Antonia J. Levi'southward Introduction to Rubrics: An Assessment Tool to Save Grading Time, Convey Constructive Feedback and Promote Student Learning (Stylus, 2012) will convince yous to requite them a effort. The concept is simple: rather than having students guess what they need to do for a proficient paper, requite them a simple, straightforward outline. Even better, take them participate in creating the rubric. Stevens and Levi argue persuasively that involving students in the generation of a rubric results in a greater sense of purchase-in.

Rubrics are also specially helpful for three groups of students: outset-generation college students, students who didn't come from aristocracy high schools and students who aren't majoring in your field. In other words, the majority of your classroom can benefit from a clear, comprehensible argument of what makes for an A, C or F paper equally far as sources, arguments, mechanics and the like. And of course, rubrics needn't be express to paper grading, but tin can be employed for a diverseness of other assignments or even participation grades. Other potential benefits include reducing grading fourth dimension past avoiding writing the aforementioned thing dozens of times, also as keeping a large education staff on the same page.

Virtually historians consider personal journals as excellent primary sources, only few of my colleagues are familiar with using them as a core component of student assessment. In Periodical Keeping: How to Use Cogitating Writing for Learning, Education, Professional person Insight and Positive Change (Stylus, 2009), Dannelle D. Stevens and Joanne E. Cooper lay out the argument that grade journals requite students non simply a place to put notes, simply they also create a infinite for teacher-directed reflection on learning. Current inquiry makes it articulate that taking knowledge and connecting it with one's own feel significantly improves memory of that cognition.

Stevens and Cooper discuss a wide range of possible uses: asking students to write out summaries of the main points of each lecture at its conclusion, writing five-infinitesimal reflections after discussions, logging progress on class projects, going back to earlier entries and annotating or updating with new ideas, and then on. They besides propose a number of ways to make journal grading a breeze.

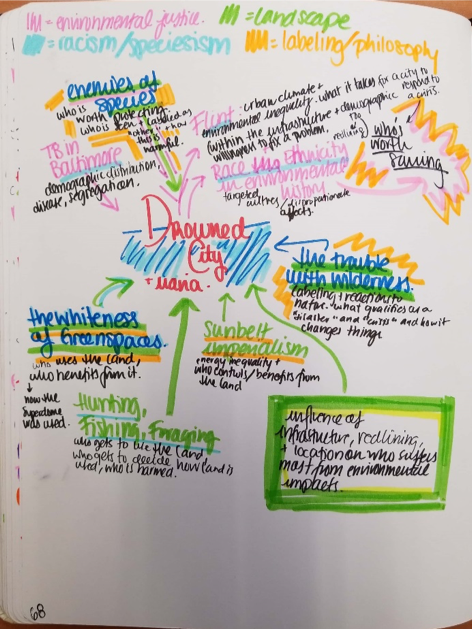

I used course journals this semester, and while the students were not unanimous in their praise, this student's words were broadly representative: "I really liked the form journals. The idea of keeping a journal for a form put me in a different listen-fix for the class, I retrieve. It opened up a space for me in my ain thinking to reflect on what we were learning and discussing as we were learning information technology, which actually enhanced my class experience." Inevitably some students will do the blank minimum, simply many others will create beautiful, richly annotated records of their learning, as the example below shows. And the authors of this book contend persuasively that all students benefit from this kind of processing.

Michele Eodice, Anne Ellen Geller and Neal Lerner -- professors at the University of Oklahoma, St. John's University and Northeastern University (respectively) -- undertook a multiyear projection in which they surveyed more than 700 students from their institutions. The professors asked if students had always completed what they considered to be a meaningful writing project, and if so, how the projection had been structured and why it had been meaningful. Their results are presented in The Meaningful Writing Projection: Learning, Teaching and Writing in Higher Pedagogy (Utah State University Printing, 2017) equally well as in a stand-alone website (here). The authors discovered that the projects students found meaningful shared three mutual characteristics: 1) students had choice for the topic but also thorough, clear prompts, two) the projects were connected to the students' lives and interests, and 3) they were relevant to what the students planned to do afterward college.

Michele Eodice, Anne Ellen Geller and Neal Lerner -- professors at the University of Oklahoma, St. John's University and Northeastern University (respectively) -- undertook a multiyear projection in which they surveyed more than 700 students from their institutions. The professors asked if students had always completed what they considered to be a meaningful writing project, and if so, how the projection had been structured and why it had been meaningful. Their results are presented in The Meaningful Writing Projection: Learning, Teaching and Writing in Higher Pedagogy (Utah State University Printing, 2017) equally well as in a stand-alone website (here). The authors discovered that the projects students found meaningful shared three mutual characteristics: 1) students had choice for the topic but also thorough, clear prompts, two) the projects were connected to the students' lives and interests, and 3) they were relevant to what the students planned to do afterward college.

Some readers may want to skip the chapters on the report's methods, jumping direct from the introduction to the conclusion. The book'south last chapter functions every bit a powerful blueprint for shaping writing assignments that build educatee motivation and make for memorable and meaningful learning experiences.

The last realm of learning inquiry, digital teaching, tin seem forbidding, with its steep learning curves and unfamiliar language. Luckily, in that location are helpful and cogent guides to the digital realm. Michelle D. Miller'due south Minds Online: Teaching Effectively With Technology (Harvard, 2016) presents a variety of ways to engage students both inside and outside the classroom.

Miller's argument is substantially twofold: judicious apply of classroom technologies ways amend learning for students and less piece of work for instructors. Her volume gives splendid suggestions for making better utilize of learning management systems like Canvas, Moodle and Blackboard; experimenting with existent-time polling; and encouraging digital-born projects for form assessments. Like Lang's book discussed to a higher place, each suggestion is reinforced with recent pedagogical research.

Before I read Minds Online, I used my Canvas sites mainly every bit repositories for PDFs of readings. And then I read how the testing result -- which shows that students asked to recall information think it improve -- embodied in depression-stakes quizzes could help students internalize class material. I fabricated simple quizzes online that asked students about the core ideas from their readings. They could retake these quizzes every bit many times every bit necessary, while only the highest grade counted. Because the quizzes were on Canvas, I never had to practise any grading; students were pleased considering they could always get a perfect score as long as they took the fourth dimension to retake the quiz.

In a sense, all academics are jugglers -- we accept to keep xanthous (teaching), blue (inquiry) and reddish (service) balls in the air at the same fourth dimension that administrators are lobbing us e'er more balls. These books accept had a transformative effect on my educational activity. Each presents research about learning and suggests easily implementable ways to modify upwardly educational activity for the better, giving instructors an edge without distracting from the perpetual juggling of our academic careers.

Source: https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2019/02/26/new-instructor-recommends-six-books-pedagogy-and-teaching-opinion

0 Response to "Books a College Professor Should Read on Teaching"

Post a Comment